I am a devoted rereader. Give me a Brontë or an Austen for the nth time and I am intoxicated. My most extreme rereading phase was the decade when I began War and Peace every New Year’s Day and finished by the next New Year’s Eve.

Occasionally I reread a book I dislike. What did I miss, I wonder, when everyone else is crazy about it? I recently failed to finish a rereading of Joan Didion’s 1970 novel Play It As It Lays, which I have been assured is a masterpiece. Beautiful prose, but perhaps better-employed in her stunning essays.

In Play It As It Lays, the wilted heroine, Maria (pronounced Ma-rye-uh), is so limp she can barely get off the patio where she sleeps under towels. She spends her days speeding along the freeway and having a nervous breakdown. If she isn’t on the freeway by ten, she loses her rhythm, she informs us. As a non-driver, I was annoyed when she kicked off her sandals to feel her bare feet on the pedal as she zooms at 100 miles an hour.

In Play It As It Lays, the wilted heroine, Maria (pronounced Ma-rye-uh), is so limp she can barely get off the patio where she sleeps under towels. She spends her days speeding along the freeway and having a nervous breakdown. If she isn’t on the freeway by ten, she loses her rhythm, she informs us. As a non-driver, I was annoyed when she kicked off her sandals to feel her bare feet on the pedal as she zooms at 100 miles an hour.

“Just give her a ticket,” I muttered.

The novel is not Didion’s forte.

I recently reread some of Didion’s essays, and found them extremely conservative, though I’d admired them on a first reading. Her essays on the Women’s Movement of the 1970s and Doris Lessing are so venomous they made my hair stand on end. And I no longer consider her stylized essay, “Slouching towards Bethlehem,’ a masterpiece. Somehow, I no longer share her point-of-view.

A rereading gone wrong.

Back to rereading: there are avid rereaders, and other readers who fiercely disapprove of rereading. Tom Lamont at The Observer is in my camp, though he is something of an apologist. He says “Rereading is therapy, despite the accompanying dash of guilt, and I find it strange that not everybody does it. Why wouldn’t you go back to something good? I return to these novels for the same reason I return to beer, or blankets or best friends.”

Back to rereading: there are avid rereaders, and other readers who fiercely disapprove of rereading. Tom Lamont at The Observer is in my camp, though he is something of an apologist. He says “Rereading is therapy, despite the accompanying dash of guilt, and I find it strange that not everybody does it. Why wouldn’t you go back to something good? I return to these novels for the same reason I return to beer, or blankets or best friends.”

Peter Damien at Book Riot shares my philosophy that a reader can appreciate a book more on a second or third or whatever reading.

I re-read endlessly, and I think of it as nothing different than reading a book for the first time. I maintain a reading journal of books I’ve read and how long it’s taken me, and there are many titles repeated throughout the journal. I don’t differentiate them. I think it’s as completely integral to the reading process as the first time through a book.”

The Pulitzer Prize-winning critic Michael Dirda at The Washington Post is not a fan of rereading. The only time he rereads is when he is teaching a book or writing an introduction for a book. He writes, “I loved Murasaki Shikibu’s The Tale of Genji, but could the analogous Chinese classic, Cao Xueqin’s The Story of the Stone, be just as good? Like Rikki-Tikki-Tavi, I want to run and find out.”

Tom Thurston at The Guardian believes rereading is pretentious. In fact, he doesn’t believe people really reread. He thinks they say it to show off.

… nothing will make you more insecure than the person who casually drops it into conversation that this summer, as well as a couple of weighty war histories, Julian Barnes’s latest and a fascinating new translation of the Qur’an, he’ll be re-reading Anna Karenina. While it doesn’t leave much time for snorkelling or hammock snoozing after a good lunch, there’s no reason why people shouldn’t choose to bury themselves under a pile of books on holiday. But there is one little verb that’s inexcusable, wherever you are, whatever you’re reading this summer. “Re-read”. Now hear this: anyone who talks about re-reading a book is arrogant, narrow-minded or dim.

Wow, he is fierce!

Do you enjoy rereading? If so, what? If not, why not?

I was in the mood to read Guy de La Bedoyere’s Domina:

I was in the mood to read Guy de La Bedoyere’s Domina: And now I’ll have to read my Greek in strong sunshine with a bright lamp haloing my head. I can think of no alternative.

And now I’ll have to read my Greek in strong sunshine with a bright lamp haloing my head. I can think of no alternative. I am an avid rereader, as readers of this blog know.

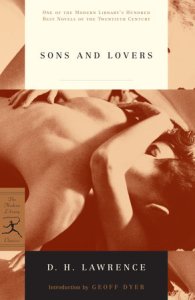

I am an avid rereader, as readers of this blog know. Gornick fell in love with D. H. Lawrence’s elegant autobiographical third novel, Sons and Lovers, at the age of 20, as so many of us do. But each reading brought with it a different perspective. Reading it

Gornick fell in love with D. H. Lawrence’s elegant autobiographical third novel, Sons and Lovers, at the age of 20, as so many of us do. But each reading brought with it a different perspective. Reading it

The Iowa Caucus is over. There will be no more political flyers in the mail. The Democratic candidates have flown to New Hampshire.

The Iowa Caucus is over. There will be no more political flyers in the mail. The Democratic candidates have flown to New Hampshire.

During a recent illness, I sweated, ached, and slept,

During a recent illness, I sweated, ached, and slept, Best-known for Stoner, a kind of tepid imitation of the lesser work of Willa Cather, Williams is more ambitious in Augustus, which won the National Book Award in 1973. (He shared the award with John Barth for Chimera.) Centered on the life of Octavian, the first Roman emperor, who was later known as Augustus, this intelligent novel unfolds in the form of pitch-perfect letters, documents, memoirs, journals, and even a stilted “lost poem” by Ovid (Williams is not much of a poet).

Best-known for Stoner, a kind of tepid imitation of the lesser work of Willa Cather, Williams is more ambitious in Augustus, which won the National Book Award in 1973. (He shared the award with John Barth for Chimera.) Centered on the life of Octavian, the first Roman emperor, who was later known as Augustus, this intelligent novel unfolds in the form of pitch-perfect letters, documents, memoirs, journals, and even a stilted “lost poem” by Ovid (Williams is not much of a poet).

It is a beautiful weekend, characterized by melting snowmen and snow-women. Alas, I have a touch of the flu.

It is a beautiful weekend, characterized by melting snowmen and snow-women. Alas, I have a touch of the flu. Do you like historical mysteries? You’ll enjoy Tasha Alexander’s In the Shadow of Vesuvius, the latest in her beautifully-written Lady Emily series. Set in the ruins of Pompeii, it alternates stories in two timelines: Lady Emily’s investigation of a murder in Pompeii in 1902, and a woman poet’s experiences and frustrations in 79 A.D..

Do you like historical mysteries? You’ll enjoy Tasha Alexander’s In the Shadow of Vesuvius, the latest in her beautifully-written Lady Emily series. Set in the ruins of Pompeii, it alternates stories in two timelines: Lady Emily’s investigation of a murder in Pompeii in 1902, and a woman poet’s experiences and frustrations in 79 A.D.. DO YOU KNOW WHO YOUR FRIENDS ARE?

DO YOU KNOW WHO YOUR FRIENDS ARE?