Staying home is a small price to pay for safety. It is like having a bodyguard, only it’s not human: a house, a rented room, an apartment, a geodesic dome, whatever shelter we have. Here’s a typical day in the spring of Covid-19: we read our books, check the news, watch TV, check the news, clean the house, check the news. It is a privileged boredom. Think of the homeless. Think of the emptying food banks.

But everyone is in shape, finally! Whenever we’re claustrophobic, we go outside. The parks, of course, are closed, so when a friend snuck into an empty park to play Frisbee, the police sent him/her home. And here’s a very strange story: a mall outside of Omaha claims it will open next week. I joked, “We’ll be there.”

Business Insider says, “More than 13,000 Americans died last week from COVID-19, surpassing past weekly averages for other common causes of death like heart disease and cancer.”

Let us hope coronavirus goes away soon.

Fortunately there are still good books to read.

Fortunately there are still good books to read.

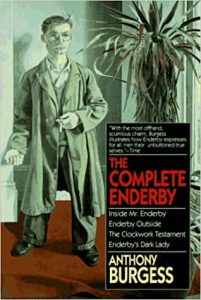

ANTHONY BURGESS’S ENDERBY NOVELS. This quartet of comical novels, Inside Mr. Enderby, Enderby Outside, The Clockwork Testament, and Enderby’s Dark Lady, is delightfully quirky. I urge you to read them if you need light relief. Burgess tells the story of Enderby, a dyspeptic English poet who writes poetry in the lavatory, frequently using the toilet paper roll as a pencil holder and writing on toilet paper. In the first novel, he is fatally seduced away from his lavatory writing by an ambitious woman, Vesta Bainbridge, whom he unhappily marries–it ends badly. In the second novel, Outside Enderby, which I just reread, he has supposedly been cured of poetry by a psychiatrist: he has metamorphosed into a bartender named Hogg. When a pop star, Yod Crewsley, celebrates publishing a book of poetry at a party at the bar, Enderby is astonished to realize the poems are plagiarized: he had composed them while living with Vesta, who is now married to the pop star. And then a disgruntled former manager shoots Crewsley, leaving Enderby with the smoking gun. His flight from the police to Tangier is hialrious, and at least his poetic muse speaks again in the muddle that follows.

ANTHONY BURGESS’S ENDERBY NOVELS. This quartet of comical novels, Inside Mr. Enderby, Enderby Outside, The Clockwork Testament, and Enderby’s Dark Lady, is delightfully quirky. I urge you to read them if you need light relief. Burgess tells the story of Enderby, a dyspeptic English poet who writes poetry in the lavatory, frequently using the toilet paper roll as a pencil holder and writing on toilet paper. In the first novel, he is fatally seduced away from his lavatory writing by an ambitious woman, Vesta Bainbridge, whom he unhappily marries–it ends badly. In the second novel, Outside Enderby, which I just reread, he has supposedly been cured of poetry by a psychiatrist: he has metamorphosed into a bartender named Hogg. When a pop star, Yod Crewsley, celebrates publishing a book of poetry at a party at the bar, Enderby is astonished to realize the poems are plagiarized: he had composed them while living with Vesta, who is now married to the pop star. And then a disgruntled former manager shoots Crewsley, leaving Enderby with the smoking gun. His flight from the police to Tangier is hialrious, and at least his poetic muse speaks again in the muddle that follows.

The third book is equally funny, as I remember, but I am pretty sure I haven’t read the fourth. It is Burgess’s convoluted, poetic language that makes Enderby stand out from other satires about writers. And, let’s face it, what is a funnier subject than a poet? I do love Enderby.

Enderby’s poems are stunning, too.

LOUISE ERDRICH’S new novel, THE NIGHT WATCHMAN, is partly political, partly a poignant tribute to the resilience of American Indian identity. Inspired by the life of Erdrich’s grandfather, Patrick Gourneau, a chief of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, it tells the story of a tribe in crisis and their political organization to prevent Congress from disbanding them and taking their land in the 1950s.

There are two main threads: the hero, Thomas Wazhashk, a night watchman at a factory, organizes the fight against termination. Thomas is charming, funny, shrewd, and spiritual: he has encounters with a snowy owl, a ghost, and spirtis in the sky. The other thread follows Pixie (Patrice), Thomas’s niece, a very smart high school graduate who is a skilled worker at a factory and determined to rise through the ranks. But life is a struggle: she supports her mother and younger brother financially, and plays the masculine role in the family, chopping wood, hunting game, and contriving to clothe and fee them. The whole family grieves over the disappearance of Patrice’s older sister Vera, who has disappeared in Minneapolis. The fight against Congress and the search for Vera are skillfully intertwined.

There are two main threads: the hero, Thomas Wazhashk, a night watchman at a factory, organizes the fight against termination. Thomas is charming, funny, shrewd, and spiritual: he has encounters with a snowy owl, a ghost, and spirtis in the sky. The other thread follows Pixie (Patrice), Thomas’s niece, a very smart high school graduate who is a skilled worker at a factory and determined to rise through the ranks. But life is a struggle: she supports her mother and younger brother financially, and plays the masculine role in the family, chopping wood, hunting game, and contriving to clothe and fee them. The whole family grieves over the disappearance of Patrice’s older sister Vera, who has disappeared in Minneapolis. The fight against Congress and the search for Vera are skillfully intertwined.

Gorgeous, lyrical writing, resilient characters, and a narrative interwoven with magic realism, ghosts, and unexpected events.