“The bad time had been going on for- but one of the qualities of a bad time is that it seems endless”–Doris Lessing’s The Four-Gated City

One summer evening when I was sixteen, I found myself eating dinner at a posh house in Westchester County, New York. The 32-year-old lesbian teacher with whom I lived (she’d seduced me, I realized later, because I was not living with my parents) was visiting her wealthy ex-father-in-law. First we went on a “tour” of his house, which was not quite the Metropolitan Museum of Art; but he pontificated about a few framed prints on the walls. Later, the European housekeeper served us dinner, something simple, perhaps chicken.

It was a difficult, nearly intolerable situation. He radiated disapproval, and in retrospect, I understand that it is far from ideal for an ex-daughter-in-law-turned-lesbian to show up with a teenage girlfriend. And the butler at his dark New York penthouse, where we had stayed a few days, had reported that we didn’t let him cook for us. The lesbian, whom I will henceforth call Hilda, was on a steak diet, so had cooked for herself. Her ex-father-in-law found this absurd. I remember little else about the conversation, except I said I liked Doris Lessing’s books, and he informed me that he “couldn’t read her; her writing was flat-footed.”

On this particular trip, I became resigned to disapproval. A few days earlier, in a small college town in the Midwest, Hilda’s professor brother had stormed out of the house and refused to speak to her after he saw she was dating a child. His wife and daughters were kind, trying to save the relationship, I suppose. But there was something definitely wrong with Hilda: she confided she was “attracted to” one of her nieces.

I felt trapped by Hilda, and also felt bored: my close friends knew all about her (“We thought she was a dirty old woman,” one of them told me years later), but I had to keep the dark secret at school, because she told me it was illegal, and she would get fired from her job; and, to make things worse, I always had a yeast infection. (I never had another after I left.) To show you how far I was from any semblance of maturity, my friends and I used to bicycle at night and hang glittered tampons (feminist art) on trees.

During this period of anxious cohabitation with Hilda, Doris Lessing’s Martha Quest novels saved me. That will sound like an exaggeration, but the books were a lifeline. Not only did I become the character when I read; I became the books. Martha, the heroine of Lessing’s five-book Children of Violence series, was my role model, and everybody else’s, as I learned when I was older.

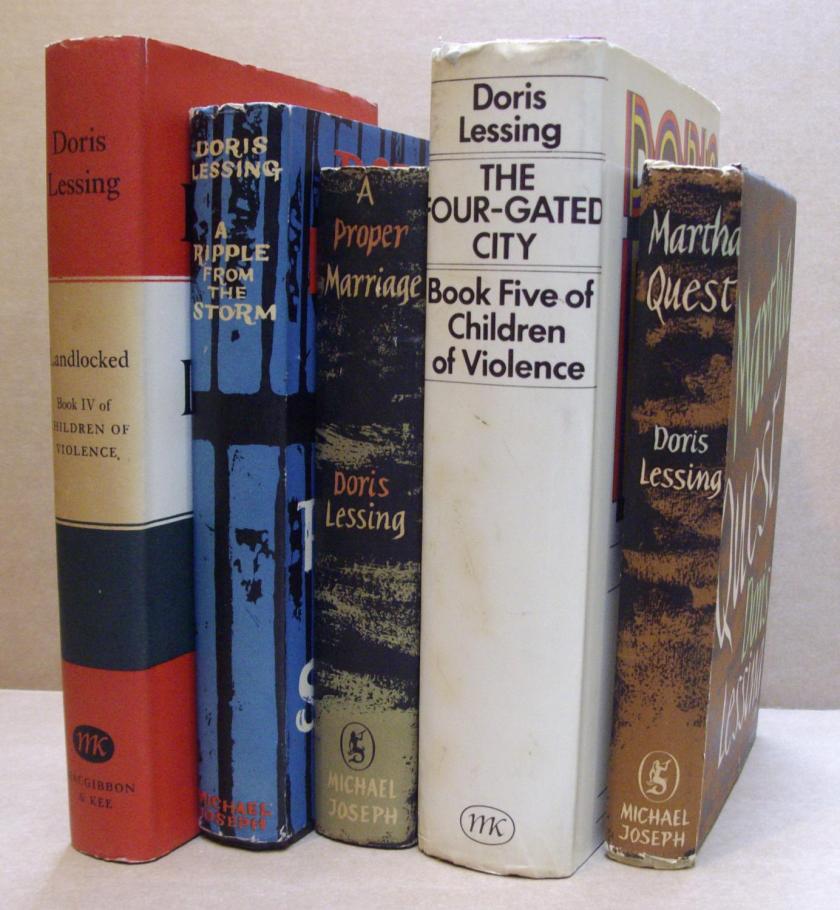

Martha encourges us to resist and struggle out of traps. In many ways, she is an escape artist, trying on roles and rejecting them. The cycle of books, Martha Quest, A Proper Marriage, A Ripple from the Storm, Landlocked, and The Four-Gated City, delineates Martha’s experiences from her teens and young adulthood in Africa, and, finally, in the last novel, she immigrates to London, where she lives into old age–until a disaster makes London a dystopia.

From the beginning, Martha is a resister. In Zambesia, a fictitious name for Southern Rhodesia, the white-dominated colony in Africa where Lessing grew up, we first meet 15-year-old Martha, a dropout who spends her days reading Kinsey, Freud, and Marx. After battling her controlling mother, she moves to town, where she becomes a secretary, and attends”sundowners” at the country club every night. Soon she is astonished to find herself married to a dull man and the bored mother of a toddler, Caroline. She leaves the marriage and her daughter, feeling guilty about Caroline, but convinced she has set Caroline free–and maybe she has, because Martha was so unhappy.

The next three books concentrate on politics and sex (which is mostly bad, alas), as Martha struggles to escape the deadening conformity of a provincial, racist, sexist society. Martha, a member of the Communist party, does her typing job between meetings and lectures, and is always sleep-deprived (it makes me tired just to read it). Lessing’s descriptions of the leftist group dynamics and political jargon are fascinating and familiar; there are countless fights and complex sexual interactions, just as there are today. And yet Martha makes another tragic mistake: she marries Anton Hesse, a German refugee and a leader of their Communist group, so he won’t be interned or deported. The two are sexually incompatible, and she is once again trapped. But once again she escapes: In the fourth novel, Landlocked, she has great sex with a charming married farmer who she knows will never leave his wife. Finally, Martha! But Martha has always meant to go to London, and finally she does.

The first four books are starkly realistic, an African coming-of-age story, and of these Landlocked is by far the best. But the last, The Four-Gated City, an experimental novel, is the one I’ve returned to agains and again. It not only charts the changing politics of post-war London but the changing trends and styles during the ’50s and ’60s. In the last part, Lessing turns London into dystopia, after an unknown disaster strikes the world.

Why did The Four-Gated City speak to me? Is it because I was trapped, and Martha gets out of her trap? Back then, we were gloomy about the bomb, the environment, overpopulation, etc. I could only too easily imagine a dystopian catastrophe, but The Four-Gated City does offer some hope.

Why did The Four-Gated City speak to me? Is it because I was trapped, and Martha gets out of her trap? Back then, we were gloomy about the bomb, the environment, overpopulation, etc. I could only too easily imagine a dystopian catastrophe, but The Four-Gated City does offer some hope.

Certainly Martha knows we need dreams to survive, though she leads an extremely difficult life. At one point, Martha and Mark, her employer in London, a writer and factory owner, discuss an ideal city. Mark begins describing it to tease her out of bad humor.

“Do you know what it is you’re really wanting, Martha? ’

And he proceeded to tell her. She was seeking, without knowing it for the mythical city, the one which appeared in legends and in fables and fairy stories, and (here he laughed at her, but affectionately) it was a hierarchic city, which is why she refused even to consider it. He proceeded to describe it, as clearly as if he had lived there; and she, laughing affectionately at him, who knew this archetypal city so well yet said he believed in nothing but a recurring destruction and disorder joined him in a long, detailed, fantastic reconstruction which, by the time they had finished, was as good as a blueprint to build.”

I left Hilda when I was eighteen. My mythical city turned out to be books, boyfriends (I married the man I loved), and taking walks in the country.

And though life is always a struggle, it helps to read Doris Lessing. Really, it does.

I came to Lessing too late in life, I think. You probably need to ‘meet’ her as a young woman. Perhaps I should look at some of her later work. I do remember enjoying The Good Terrorist.

She’s a force; people have strong feelings about her. Love or hate, nothing in between with Lessing!

What an experience: how fortunate we have been to have discovered books and stories when the real world was so often hard and sad! Coincidentally, I picked up a sweet old copy of Martha Quest in a LFL not long ago. It’s interesting, though, that it’s the final, more experimental novel, which has called you back to it repeatedly. I’ll keep that in mind.

The Martha Quest books are my favorites! A Four-Gated City could probably be read on its own, because it is about Martha’s experiences in London after Africa. Lessing put everything she knew into this book: the Cold War, the fashions in literary life that make a novel popular or unpopular in different times, the rise of popular protest after years of May Day marches ignored by the press, mental illness interpretations, and finally SF!