Happy New Year! Let’s hope 2026 will be a terrific reading year!

Here is Part II of my Year in Books, July to December.

July 2025

Carol Shields’ The Box Garden. The Pulitzer Prize-winning Carol Shields’The Box Garden is is a gentle comedy. She breezily sketches family problems in the context of a domestic comedy. Charleen, a poet and part-time assistant editor at a botanical journal, attends her 70-year-old mother’s wedding in Toronto with her dentist boyfriend, whom friends consider unhip. Her ex-husband left her to live in a commune near Toronto: she intends to track him down. And she has a crush on her penpal, a man whose philosophical essay on grass was rejected by the botanical journal.

Charming, sweet, and funny.

August 2025

Set in the 16th century, Allegra Goodman’s stunning historical novel, Isola, is part coming-of-age story, part survival story. The heroine, Marguerite de la Rocque, orphaned at the age of three, inherited a fortune and lives comfortably with her nurse. Then her guardian, Jean-François Roberval, squanders all her money and sells her house. He insists that Marguerite and her nurse accompany him on a sea voyage to New France (Canada). At sea, in sight of the shores of Canada, he dumps Marguerite, his secretary, who has become Marguerite’s lover, and her elderly nurse on an uninhabited island. Based on real events, this novel is an elegantly-written page-turner.

September 2025

Fanny Burney’s 941-page novel Cecilia, her masterpiece, was one of the pleasures of the year. Burney (1752-1840) influenced Jane Austen, who took the title, Pride and Prejudice, from a passage in Cecilia. Each of Burney’s lively sentences is exquisite, the narrative is lively, and the saucy dialogue made me laugh. Burney portrays silly rich people living on the edge of bankruptcy, glitzy, decadent parties, and suitors who want to marry her for money. Cecilia is not a typical heroine: she is not interested in marriage. She fobs off the suitors! What next?

October 2025

Jean Rhys’s After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie is a novel of desperation. Rhys’s style is so spare that it complements the heroine’s bare, squalid life. Julia, a rich man’s ex-mistress, doesn’t know how to survive on her own. . Her beauty is waning, she has no job, she seldom leaves her hotel room, and in the evening drinks a little too much in cafes, often with strange men. After Mr. Mackenzie’s lawyer informs her that there will be no more checks, she teeters on the edge of prostitution. What can she do?

November 2025

Joseph Conrad’s short, dense political novel, The Secret Agent, is a spy story, but it also charts the the destruction of the nuclear family. Mr. Verloc runs a porn shop as a cover for his work as an anarchist and second job as a secret agent. His young wife, Winnie, helps with the shop and takes care of her mentally disabled brother Stevie. Surprisingly, Mr. Verloc finds a way to use Stevie: he becomes the unknowing agent of Mr. Verloc, after Privy Councilor Wurmt of the Russian embassy orders Verloc to commit a radical action to rouse the public against anarchists. Beware of the twisted plots of double agents!

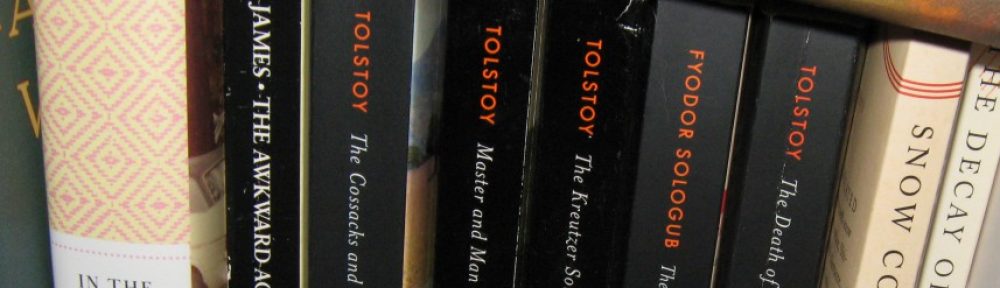

In Henry James’ convoluted novel, The Awkward Age, there is very little action. Much of the plot unfolds in oblique dialogue. At her salon, Mrs. Brookenham sighs over the fate of her attractive daughter, Nanda, who knows too much for a marriageable woman, and, as a duchess says to Mrs. Brookenham, will drive away eligible men. Mrs. Brookenham is ambivalent toward her daughter: she is competing with Nanda for the admiration of her friend, Mr. Vandenbank. But nothing goes terribly wrong until Mr. Longdon, a stodgy man in his fifties, arrives in London to research the history of Lady Julia, who was Mrs. Brookenham’s late mother.

A compelling novel, written in Henry James’ incomparable, convoluted style.