If you’re in holiday despair, if your industrial-farm turkey didn’t roast properly (the chemicals make it rubbery), if you got the wrong kind of cranberry sauce, there is only one solution: go live in the woods.

The good news: Henry David Thoreau did it first. He lived simply in his cabin by Walden Pond. “I would rather sit on a pumpkin and have it all to myself than be crowded on a velvet cushion,” he writes in Walden. That seemed profound when I was a young woman.

Nowadays, sitting on a pumpkin sounds very Cinderella. Was her coach a pumpkin? I honestly can’t remember. But sitting on a pumpkin sounds uncomfortable. How large was this pumpkin? Did it come in small, medium, and large? Could you put a velvet cushion on top?

There is a lagoon not far from us, but it is not Walden pond. It is murky and weedy, and the ducks live there, and if they can, I can. Except for one thing: what would my source of drinking water be? And there you’d be, ice-fishing at the lagoon, and the hikers would give you money, because they’d think you’re a homeless person living in a tent by the lagoon, and they might kindly tell you that there are no fish in the lagoon.

If you pretend to be Thoreau, as opposed to Cinderella, many will condemn you as a social misfit. It’s one thing to go to the ball in a magic pumpkin and enchant a prince-husband, but it’s another to escape the trappings of capitalist society and live off the land, i.e., the lagoon.

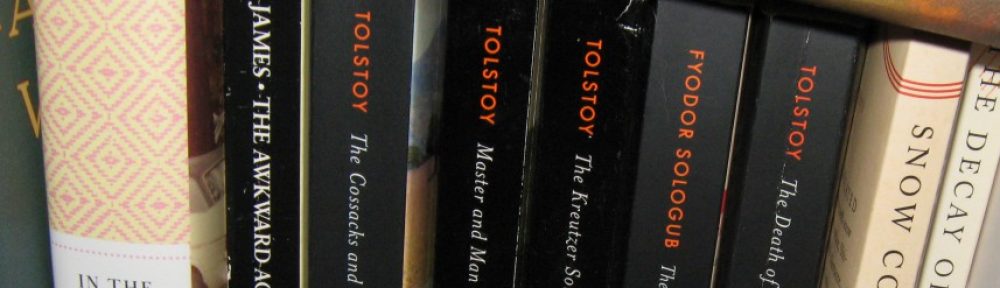

On a different note, I recommend Conrad Richter’s 1953 novel, The Light in the Forest, a compassionate novel about a young white boy, raised happily by Indians (Indigenous people) after being captured as a child. He is very close to his Indian family, but his life is ripped apart when a British edict declares that the Indians must return the captives to their white families. The story is touching, and very sympathetic to Indigenous culture. Is it right to take the boy away from his family and culture twice?

Another great book for nature lovers is Louise Rich’s We Took to the Woods (1942), a chronicle of her family’s life in a rickety house – actually a former fishing camp – in the woods in Maine. Rich takes each season as it comes. In winter, she and her family are cut off from town for months because of the snow. They stock up on canned goods, chop wood, garden, fish, occasionally hunt game, and attempt to train their affectionate huskies to pull a dog sled.

Here’s an excerpt from We Took to the Woods:

Winter, to look forward to, is a long, dark, dreary time. To live, it’s a time of swirling blizzards and heavenly high blue and white days; of bitter cold and sudden thaws; of hard work outdoors and long, lamp-lit evenings; of frost patterns on the windows and the patterns of deer tracks in the snow. It’s the time you expected to drag intolerably, and once in a while you stop and wonder when the drag is going to begin. Next week, you warn yourself, after we’ve finished doing this job on hand, we’d better be prepared for a siege of boredom. But somehow next week never comes. There’s always something to keep it at bay.

Winter is just starting here. Snow is predicted for tomorrow. Enjoy the rest of your holiday!